Large Concept Models was discussed in Janelia CVML 2025-02-07.

I’ve been interested in what temporal scales it makes sense to model time series data at. Nearly all language modeling approaches represent text at the word (token) level. There is no explicit representation of the concepts underlying text at larger scales, while it seems like our own internal representations of language exist at multiple scales. Would explicitly representing larger scales improve how well language models capture semantic concepts, model longer-range temporal relationships, even reason? Or does word-token-level modeling implicitly capture this structure?

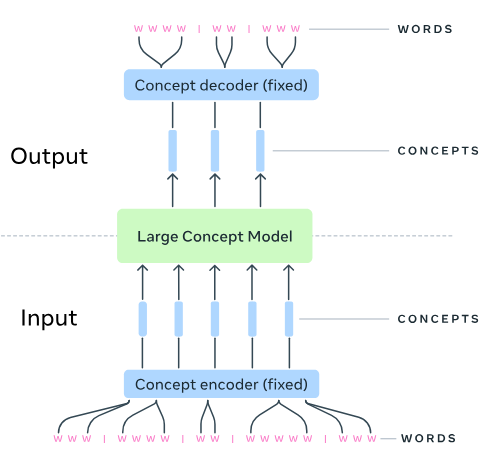

Large Concept Models is an interesting attempt at explicitly modeling structure at a larger scale: sentences. Like spaces between words, punctuation between sentences provides a non-arbitrary way to segment text at a scale ~50 times that of word tokens. This work posits that this sentence-scale representation corresponds to concepts, hence the paper title. The basic idea implemented is straightforward (Figure 1):

- Use an existing model (SONAR) to embed sentences into a “concept” space.

- Train a transformer that predicts sentence embeddings rather than word tokens.

- At inference, convert predicted sentence embeddings to text through the embedding model’s decoder.

Concepts and resolutions

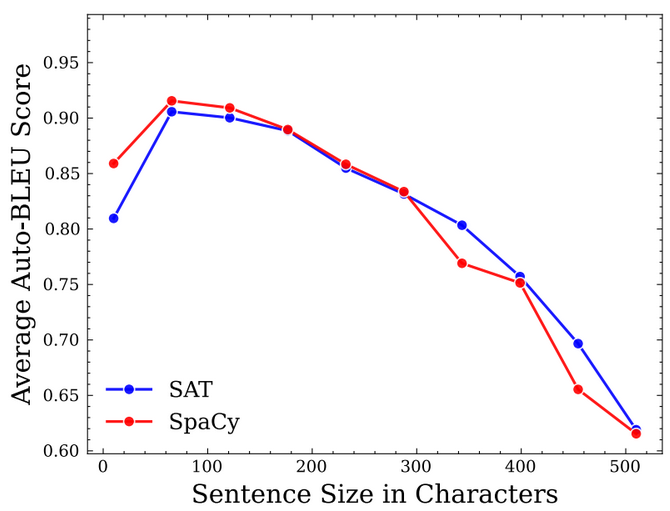

One question about this approach is the choice of resolutions. Does a sentence really correspond to a concept? Or should we rather use parts of speech? Paragraphs? Or should segmentation be something determined based on the text? Should language be modeled at many resolutions at a time? One of the details of the paper was that dividing text into sentences was non-trivial, and the method improved by capping the maximum sentence length at 200 characters, suggesting that the next level of resolution after words perhaps should be shorter than a sentence (Figure 2).

This choice could be because the sentence embedding model, SONAR [Duquenne, 2023] was “trained on … bitext machine translation data containing rather short sentences.” Since its training was targeting machine translation, it is unclear whether it encodes “concepts” or some other semantics of sentences. Future work could explore different choices for the sentence embedding, perhaps seeking to more directly encode “concepts” from sentences, or by training the encoder end-to-end, challenging though that may be.

Another question is about the integration of resolutions. The model trained here really operated only at the sentence-resolution, with the word encoder/decoder being done completely independently. Not only are the encoder and decoder fixed (as shown in Figure 1), words are not seen or produced by the LCM – both training and inference are done solely at the sentence level. Thus, this model is really a single-resolution model that operates at a larger scale than standard LLMs. This has the benefit of helping greatly with computational complexity, allowing the network to potentially reason over much longer context lengths. However, we suspect that this hurts the quality of the text produced. One caveat to this is that the proposed approaches – the diffusion LCM and quantized LCM – predict the sentence embedding with coarse-to-fine resolution, so perhaps some sub-sentence structure is also represented.

Transformers for high-d, continuous time-series data

One of the strengths of this paper are the many approaches tried for adapting transformers to model sentence embeddings, which live in a 1024-dimensional continuous space. The authors try three methods:

- The baseline LCM predicts the continuous embedding vector with a MSE loss – it does not try to model the possibly multi-modal next-sentence distribution.

- The diffusion-based LCMs use diffusion models to model this continuous distribution.

- The quantized LCMs first quantize the sentence embedding space, then predict

Diffusion LCMs - details

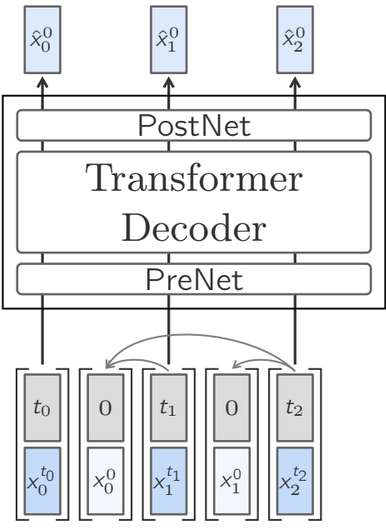

Let \(x_n\) be the \(n\)th sentence embedding and \(x_n^t\) be the embedding after \(t\) diffusion steps. This approach models the noiseless \(n\)th sentence embedding \(x_n^0\) given a noisy version \(x_n^t\) and the previous noiseless sentences \(x_{<n}^0\): \(p_\theta(x_n^0 | x_n^t, t, x_{<n}^0)\). This can be set up to train efficiently with attention masks, allowing all sentences in a document to be predicted simultaneously. There are a lot of details about all the diffusion model tricks they used, including the noise schedule, sample weighting, and classifier-free diffusion guidance. Their two-tower diffusion LCM separates the encoding of previous sentences \(x_{<n}^0\) from the denoising process from \(x_n^t\) with one transformer tower each. These details are a great resource for someone trying to train transformer-diffusion models for time series data.

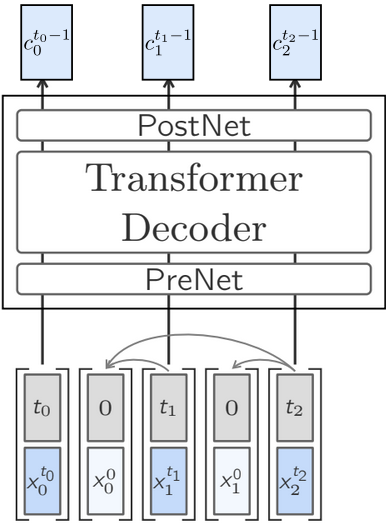

Quantized LCMs - details

Quantized LCMs first tokenize the sentence embedding space, which makes the LCM mechanically more like a standard LLM. Specifically, they use the Residual Vector Quantization which converts a sentence embedding into a sequence of 64 coarse-to-fine codewords. My guess of how this was done based on the details in the text is as follows. Let \(c_n^t\) be the \(t\)th resolution codeword for sentence \(n\), and let \(\mu^t_c\) be the \(c\)th codeword for the \(t\)th resolution codebook. Then we can construct the \(t\)th resolution approximation of our sentence embedding from codewords \((c_{T-1},...,c_0)\) as \[x_n^t = \sum_{i\geq t} \mu^i_{c_n^i}\] Then, they can do something similar to the one-tower diffusion LCM, replacing \(\hat{x}^0_n\) with \(c^{t_n+1}_n\) (Figure 4).

They also tried an approach, termed QUANT-LCM-C, where they predict the continuous target embedding from the intermediate quantized representation, and at inference time, they sample a codeword based on the distance to the predicted residual. Depending on details here, I’m not sure if, during training, the distribution is modeled, or if it is just a way to add some noise at inference time.

Coarse-to-fine predictions

A notable commonality between the diffusion LCM and quantized LCM is the coarse-to-fine resolution (\(t = T, ..., 0\)) for prediction. One question I have is whether this allows more resolutions of language between word and sentence to be represented. While these intermediate scales are part of the prediction, I note that they are not part of the left-context the transformer has access to; they are only used for the current sentence. Still, this could be an interesting avenue to explore in the future – what if they were not so clever with their attention masks (Figure 3, Figure 4), and allowed intermediate representations in the context? Would this be an avenue to a more multi-resolution language model?

Experiments

The paper includes an extensive description of experiments conducted to compare these different LCM models to each other and to word-based LLMs. One of the difficulties with language modeling in general is that there is not a single way to measure which model performs best, and the results comparing LCMs, to me, appear to be conflicting, with the baseline model performing best in terms of simple \(l_2\) distance, and diffusion models performing better for some more complex metrics while quantization methods perform better for others.

The authors conclude that “diffusion-based methods give clearly better results compared to all other models”, and I couldn’t tell what this was based on, from the tables of results provided. We noted that there isn’t a single example output in the paper, and think a good rule of thumb with ML experimental sections is you shouldn’t only have example outputs, but you also shouldn’t only have tables of bolded numbers.

One reason I could imagine the quantized LCM performing worse is because of the choice of the fixed embedding space. The sentence embedding to words decoder is likely not robust to deviations from the sub-space of the 1024-dimensional ambient embedding space that it was trained on, and the diffusion models are likely better than the quantized models at producing examples in that sub-space. By analogy, I’m thinking of how GANs produce more realistic images than VAEs but VAEs may cover the full distribution better, and I think this may be true for diffusion models vs quantized models. Perhaps a text example produced by a diffusion model is harder to distinguish from human text, but fails at capturing the full distribution. Would that be captured by any of these metrics? The authors suggest that training the embedding space to be quantize-able may improve this method.

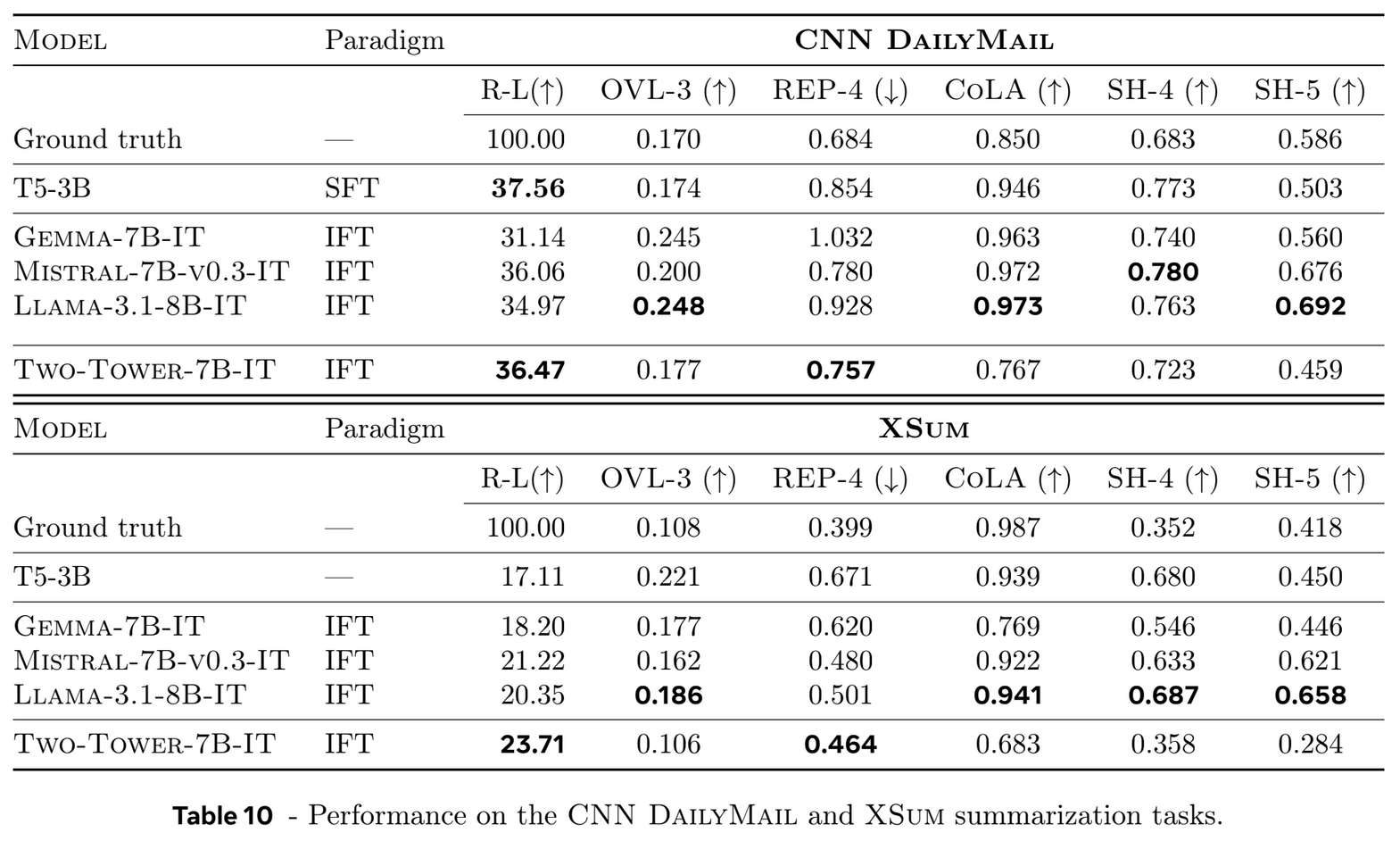

They also compare to standard, word-token-based LLMs on summarization tasks, again with conflicting results, depending on the metric. This is the disappointing part of the paper – there’s not really an obvious (to me) benefit of the sentence-resolution modeling over word-resolution modeling. Does that mean larger-scale resolutions are implicitly learned in word-resolution models, or that there is still work to do to get explicit larger-scale resolution models to work? As the authors conclude, “[t]he choice and design of the embedding space plays a crucial role”, and note differences in the data used to train the embedding space and their LCM, and potential issues with the frozen encoder.

Closing thoughts

The paper presents an interesting idea in a direction I think is promising – explicit representation of longer time scales in time-series-data modeling. I’m happy to see people working on it! It also has some creative ideas for how to use transformers to predict continuous, high-dimensional time-series data, which I plan to try out on my own data. I appreciate the detail the authors provided on many of their methods, including the tweaks they tried, even when they didn’t improve results. It was clearly a tremendous amount of work.

Ultimately, my guess from the experiments is that this method did not, on its own, improve the quality of text generated beyond what word-based LLMs produce. I’d guess that in future work, the authors or others will explore:

- Simultaneously modeling more scales during training and inference,

- Learning segmentations rather than imposing them from sentence structure,

- Jointly learning concept embeddings with the language model.

In my opinion, the question of whether explicitly modeling longer time scales is helpful for language modeling remains open and compelling!

References

[LCM Team, 2024] LCM team, Loïc Barrault, Paul-Ambroise Duquenne, Maha Elbayad, Artyom Kozhevnikov, Belen Alastruey, Pierre Andrews, Mariano Coria, Guillaume Couairon, Marta R. Costa-jussà, David Dale, Hady Elsahar, Kevin Heffernan, João Maria Janeiro, Tuan Tran, Christophe Ropers, Eduardo Sánchez, Robin San Roman, Alexandre Mourachko, Safiyyah Saleem, Holger Schwenk, “Large Concept Models: Language Modeling in a Sentence Representation Space”, 2024. 🔗, [code].

[Duquenne, 2023] Paul-Ambroise Duquenne, Holger, Schwenk, and Benoit Sagot, “SONAR: Sentence-Level Multimodal and Language-Agnostic Representations”, 2023. 🔗

[Hujben, 2024] Iris A. M. Huijben, Matthijs Douze, Matthew Muckley, Ruud J. G. van Sloun, Jakob Verbeek, “Residual Quantization with Implicit Neural Codebooks”, 2024 🔗